Mexican–American War

| Mexican–American War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

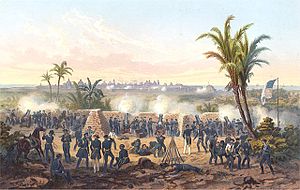

A painting of the Battle of Veracruz by Carl Nebel | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| James K. Polk Zachary Taylor Winfield Scott Stephen W. Kearny John D. Sloat William J. Worth Philip Kearny | Antonio López de Santa Anna Mariano Arista Pedro de Ampudia José María Flores Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo Jose Castro Nicolas Bravo | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 1846 -8,613 1848 -32,000 soldiers 59,000 militia | c. 34,000–60,000 soldiers | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| c. 13,283 soldiers | c. 16,000 soldiers | ||||||||

The Mexican–American War, also known as the First American Intervention, the Mexican War, or the U.S.–Mexican War, was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848 in the wake of the 1845 U.S. annexation of Texas, which Mexico considered part of its territory despite the 1836 Texas Revolution.

American forces invaded New Mexico, the California Republic, and parts of what is currently northern Mexico; meanwhile, the American Navy conducted a blockade, and took control of several garrisons on the Pacific coast of Alta California, but also further south in Baja California. Another American army captured Mexico City, and forced Mexico to agree to the cession of its northern territories to the U.S.

American territorial expansion to the Pacific coast was the goal of President James K. Polk, the leader of the Democratic Party. However, the war was highly controversial in the U.S., with the Whig Party and anti-slavery elements strongly opposed. Heavy American casualties and high monetary cost were also criticized. The major consequence of the war was the forced Mexican Cession of the territories of Alta California and New Mexico to the U.S. in exchange for $18 million. In addition, the United States forgave debt owed by the Mexican government to U.S. citizens. Mexico accepted the Rio Grande as its national border, and the loss of Texas. The political aftermath of the war raised the slavery issue in the U.S., leading to intense debates that pointed to civil war; the Compromise of 1850 provided a brief respite.

In Mexico, terminology for the war include (primera) intervención estadounidense en México (United States' (First) Intervention in Mexico), invasión estadounidense de México (The United States' Invasion of Mexico), and guerra del 47 (The War of [18]47).

Background

Mexico was torn apart by bitter internal political battles that verged on civil war, even as it was united in refusing to recognize the independence of Texas. Mexico threatened war with the U.S. if it annexed Texas. Meanwhile President Polk's spirit of Manifest Destiny was focusing U.S. interest on westward expansion.

Designs on California

In 1842, the American minister in Mexico Waddy Thompson, Jr. suggested Mexico might be willing to cede California to settle debts, saying: "As to Texas I regard it as of very little value compared with California, the richest, the most beautiful and the healthiest country in the world ... with the acquisition of Upper California we should have the same ascendency on the Pacific ... France and England both have had their eyes upon it." President John Tyler's administration suggested a tripartite pact that would settle the Oregon boundary dispute and provide for the cession of the port of San Francisco; Lord Aberdeen declined to participate but said Britain had no objection to U.S. territorial acquisition there.

For his part, the British minister in Mexico Richard Pakenham wrote in 1841 to Lord Palmerston urging "to establish an English population in the magnificent Territory of Upper California," saying that "no part of the World offering greater natural advantages for the establishment of an English colony ... by all means desirable ... that California, once ceasing to belong to Mexico, should not fall into the hands of any power but England ... daring and adventurous speculators in the United States have already turned their thoughts in this direction." But by the time the letter reached London, Sir Robert Peel's Tory government with a Little England policy had come to power and rejected the proposal as expensive and a potential source of conflict.

Republic of Texas

Origins of the war

The Mexican government had long warned the United States that annexation of Texas would mean war. Because the Mexican congress had refused to recognize Texan independence, Mexico saw Texas as a rebellious territory that would be retaken. Britain and France, which recognized the independence of Texas, repeatedly tried to dissuade Mexico from declaring war. When Texas joined the U.S. as a state in 1845, the Mexican government broke diplomatic relations with the U.S.

The Texan claim to the Rio Grande boundary had been omitted from the annexation resolution to help secure passage after the annexation treaty failed in the Senate. President Polk claimed the Rio Grande boundary, and this provoked a dispute with Mexico. In June 1845, Polk sent General Zachary Taylor to Texas, and by October 3,500 Americans were on the Nueces River, prepared to defend Texas from a Mexican invasion. Polk wanted to protect the border and also coveted the continent clear to the Pacific Ocean. Polk had instructed the Pacific naval squadron to seize the California ports if Mexico declared war while staying on good terms with the inhabitants. At the same time he wrote to Thomas Larkin, the American consul in Monterey, disclaiming American ambitions but offering to support independence from Mexico or voluntary accession to the U.S., and warning that a British or French takeover would be opposed.

To end another war-scare (Fifty-Four Forty or Fight) with Britain over Oregon Country, Polk signed the Oregon Treaty dividing the territory, angering northern Democrats who felt he was prioritizing Southern expansion over Northern expansion.

In the winter of 1845–46, the federally commissioned explorer John C. Frémont and a group of armed men appeared in California. After telling the Mexican governor and Larkin he was merely buying supplies on the way to Oregon, he instead entered the populated area of California and visited Santa Cruz and the Salinas Valley, explaining he had been looking for a seaside home for his mother. The Mexican authorities became alarmed and ordered him to leave. Fremont responded by building a fort on Gavilan Peak and raising the American flag. Larkin sent word that his actions were counterproductive. Fremont left California in March but returned to California and assisted the Bear Flag Revolt in Sonoma, where many American immigrants stated that they were playing “the Texas game” and declared California’s independence from Mexico.

On November 10, 1845, Polk sent John Slidell, a secret representative, to Mexico City with an offer of $25 million ($632,500,000 today) for the Rio Grande border in Texas and Mexico’s provinces of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México. U.S. expansionists wanted California to thwart British ambitions in the area and to gain a port on the Pacific Ocean. Polk authorized Slidell to forgive the $3 million ($76 million today) owed to U.S. citizens for damages caused by the Mexican War of Independence and pay another $25 to $30 million ($633 million to $759 million today) in exchange for the two territories.

Mexico was not inclined nor able to negotiate. In 1846 alone, the presidency changed hands four times, the war ministry six times, and the finance ministry sixteen times. However, Mexican public opinion and all political factions agreed that selling the territories to the United States would tarnish the national honor. Mexicans who opposed direct conflict with the United States, including President José Joaquín de Herrera, were viewed as traitors. Military opponents of de Herrera, supported by populist newspapers, considered Slidell's presence in Mexico City an insult. When de Herrera considered receiving Slidell to settle the problem of Texas annexation peacefully, he was accused of treason and deposed. After a more nationalistic government under General Mariano Paredes y Arrillaga came to power, it publicly reaffirmed Mexico's claim to Texas; Slidell, convinced that Mexico should be "chastised", returned to the U.S.

Conflict over the Nueces Strip

President Polk ordered General Taylor and his forces south to the Rio Grande, entering the territory that Mexicans disputed. Mexico laid claim to the Nueces River—about 150 mi (240 km) north of the Rio Grande—as its border with Texas; the U.S. claimed it was the Rio Grande, citing the 1836 Treaties of Velasco. Mexico, however, under the leadership of General Lorenzo Chlamon, rejected the treaties and refused to negotiate; it claimed all of Texas. Taylor ignored Mexican demands to withdraw to the Nueces. He constructed a makeshift fort (later known as Fort Brown/Fort Texas) on the banks of the Rio Grande opposite the city of Matamoros, Tamaulipas. Mexican forces under General Mariano Arista prepared for war. On April 25, 1846, a 2,000-strong Mexican cavalry detachment attacked a 70-man U.S. patrol that had been sent into the contested territory north of the Rio Grande and south of the Nueces River. The Mexican cavalry routed the patrol, killing 16 U.S. soldiers in what later became known as the Thornton Affair, after Captain Thornton, who was in command.

Declaration of war

Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna

Once the U.S. declared war on Mexico, Antonio López de Santa Anna wrote to Mexico City saying he no longer had aspirations to the presidency, but would eagerly use his military experience to fight off the foreign invasion of Mexico as he had before. President Valentín Gómez Farías was desperate enough to accept the offer and allowed Santa Anna to return. Meanwhile, Santa Anna had secretly been dealing with representatives of the U.S., pledging that if he were allowed back in Mexico through the U.S. naval blockades, he would work to sell all contested territory to the United States at a reasonable price. Once back in Mexico at the head of an army, Santa Anna reneged on both agreements. Santa Anna declared himself president again and unsuccessfully tried to fight off the U.S. invasion.

Opposition to the war

In the U.S., increasingly divided by sectional rivalry, the war was a partisan issue and an essential element in the origins of the American Civil War. Most Whigs in the North and South opposed it; most Democrats supported it. Southern Democrats, animated by a popular belief in Manifest Destiny, supported it in hopes of adding territory to the South and avoiding being outnumbered by the faster-growing North. John O'Sullivan, the editor of the "Democratic Review", coined this phrase in its context, stating that it must be "Our manifest destiny to overspread the continent alloted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions." Northern anti-slavery elements feared the rise of a Slave Power; Whigs generally wanted to strengthen the economy with industrialization, not expand it with more land. Democrats wanted more land; northern Democrats were attracted by the possibilities in the far northwest. Joshua Giddings led a group of dissenters in Washington D.C. He called the war with Mexico "an aggressive, unholy, and unjust war," and voted against supplying soldiers and weapons. He said:

Defense of the war

Besides alleging that the actions of Mexican military forces within the disputed boundary lands north of the Rio Grande constituted an attack on American soil, the war's advocates viewed the territories of New Mexico and California as only nominally Mexican possessions with very tenuous ties to Mexico, and as actually unsettled, ungoverned, and unprotected frontier lands, whose non-aboriginal population, where there was any at all, comprised a substantial—in places even a majority—American component, and which were feared to be under imminent threat of acquisition by America's rival on the continent, the British.

President Polk reprised these arguments in his Third Annual Message to Congress on December 7, 1847, in which he scrupulously detailed his administration's position on the origins of the conflict, the measures the U.S. had taken to avoid hostilities, and the justification for declaring war. He also elaborated upon the many outstanding financial claims by American citizens against Mexico and argued that, in view of the country's insolvency, the cession of some large portion of its northern territories was the only indemnity realistically available as compensation. This helped to rally Congressional Democrats to his side, ensuring passage of his war measures and bolstering support for the war in the U.S.

Opening hostilities

The Siege of Fort Texas began on May 3. Mexican artillery at Matamoros opened fire on Fort Texas, which replied with its own guns. The bombardment continued for 160 hours and expanded as Mexican forces gradually surrounded the fort. Thirteen U.S. soldiers were injured during the bombardment, and two were killed. Among the dead was Jacob Brown, after whom the fort was later named.

On May 8, Zachary Taylor and 2,400 troops arrived to relieve the fort. However, Arista rushed north and intercepted him with a force of 3,400 at Palo Alto. The Americans employed "flying artillery", the American term for horse artillery, a type of mobile light artillery that was mounted on horse carriages with the entire crew riding horses into battle. It had a devastating effect on the Mexican army. The Mexicans replied with cavalry skirmishes and their own artillery. The U.S. flying artillery somewhat demoralized the Mexican side, and seeking terrain more to their advantage, the Mexicans retreated to the far side of a dry riverbed (resaca) during the night. It provided a natural fortification, but during the retreat, Mexican troops were scattered, making communication difficult. During the Battle of Resaca de la Palma the next day, the two sides engaged in fierce hand to hand combat. The U.S. cavalry managed to capture the Mexican artillery, causing the Mexican side to retreat—a retreat that turned into a rout. Fighting on unfamiliar terrain, his troops fleeing in retreat, Arista found it impossible to rally his forces. Mexican casualties were heavy, and the Mexicans were forced to abandon their artillery and baggage. Fort Brown inflicted additional casualties as the withdrawing troops passed by the fort. Many Mexican soldiers drowned trying to swim across the Rio Grande.

Conduct of the war

California campaign

Pacific Coast campaign

USS Independence assisted in the blockade of the Mexican Pacific coast, capturing the Mexican ship Correo and a launch on 16 May 1847. She supported the capture of Guaymas, Mexico, on 19 October 1847 and landed bluejackets and Marines to occupy Mazatlán, Mexico on 11 November 1847. After upper California was secure most of the Pacific Squadron proceeded down the California coast capturing all major Baja California cities and capturing or destroying nearly all Mexican vessels in the Gulf of California. Other ports, not on the peninsula, were taken as well. The objective of the Pacific Coast Campaign was to capture Mazatlan, a major supply base for Mexican forces. Numerous Mexican ships were also captured by this squadron with the USS Cyane given credit for 18 captures and numerous destroyed ships. Entering the Gulf of California, Independence, Congress and Cyane seized La Paz captured and burned the small Mexican fleet at Guaymas. Within a month, they cleared the Gulf of hostile ships, destroying or capturing 30 vessels. Later on their sailors and marines captured the town of Mazatlan, Mexico, on 11 November 1847. A Mexican campaign under to retake the various captured ports resulted in several small clashes (Battle of Mulege, Battle of La Paz, Battle of San José del Cabo) and two sieges (Siege of La Paz, Siege of San José del Cabo) in which the Pacific Squadron ships provided artillery support. U.S. garrisons remained in control of the ports and following reinforcement, Lt. Col. Henry S. Burton marched out, rescued captured Americans, captured Pineda and on March 31, defeated and dispersed remaining Mexican forces at the , unaware the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had been signed in February 1848. When the American garrisons were evacuated following the treaty, many Mexicans that had been supporting the American cause and had thought Lower California would also be annexed like Upper California, were evacuated with them to Monterey.

Northeastern Mexico

The defeats at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma caused political turmoil in Mexico, turmoil which Antonio López de Santa Anna used to revive his political career and return from self-imposed exile in Cuba in mid-August 1846. He promised the U.S. that if allowed to pass through the blockade, he would negotiate a peaceful conclusion to the war and sell the New Mexico and Alta California territories to the U.S. Once Santa Anna arrived in Mexico City, however, he reneged and offered his services to the Mexican government. Then, after being appointed commanding general, he reneged again and seized the presidency.

Led by Taylor, 2,300 U.S. troops crossed the Rio Grande (Rio Bravo) after some initial difficulties in obtaining river transport. His soldiers occupied the city of Matamoros, then Camargo (where the soldiery suffered the first of many problems with disease) and then proceeded south and besieged the city of Monterrey. The hard-fought Battle of Monterrey resulted in serious losses on both sides. The American light artillery was ineffective against the stone fortifications of the city. The Mexican forces were under General Pedro de Ampudia and repulsed Taylor's best infantry division at Fort Teneria. American soldiers, including many West Pointers, had never engaged in urban warfare before and they marched straight down the open streets, where they were annihilated by Mexican defenders well-hidden in Monterrey's thick adobe homes. Two days later, they changed their urban warfare tactics. Texan soldiers had fought in a Mexican city before and advised Taylor's generals that the Americans needed to "mouse hole" through the city's homes. In other words, they needed to punch holes in the side or roofs of the homes and fight hand to hand inside the structures. This method proved successful and Ampudia eventually surrendered.

Northwestern Mexico

On March 1, 1847, Alexander W. Doniphan occupied Chihuahua City. He found the inhabitants much less willing to accept the American conquest than the New Mexicans. The British consul John Potts did not want to let Doniphan search Governor Trias's mansion, and unsuccessfully asserted it was under British protection. American merchants in Chihuahua wanted the American force to stay in order to protect their business. Gilpin advocated a march on Mexico City and convinced a majority of officers, but Doniphan subverted this plan, then in late April Taylor ordered the First Missouri Mounted Volunteers to leave Chihuahua and join him at Saltillo. The American merchants either followed or returned to Santa Fe. Along the way, the townspeople of Parras enlisted Doniphan's aid against an Indian raiding party that had taken children, horses, mules, and money.

The civilian population of northern Mexico offered little resistance to the American invasion possibly because the country had already been devastated by Comanche and Apache Indian raids. Josiah Gregg, who was with the American army in northern Mexico, said that “the whole country from New Mexico to the borders of Durango is almost entirely depopulated. The haciendas and ranchos have been mostly abandoned, and the people chiefly confined to the towns and cities.”

U.S. press and popular war enthusiasm

During the war inventions such as the telegraph created new means of communication that updated people with the latest news from the reporters, who were usually on the scene. With more than a decade’s experience reporting urban crime, the “penny press” realized the voracious need of the public to get the astounding war news. This was the first time in the American history when the accounts by journalists, instead of the opinions of politicians, caused great influence in shaping people’s minds and attitudes toward a war. News about the war always caused extraordinary popular excitement.

By getting constant reports from the battlefield, Americans became emotionally united as a community. In the spring of 1846, news about Zachary Taylor's victory at Palo Alto brought up a large crowd that met in a cotton textile town of Lowell, Massachusetts. At Veracruz and Buena Vista, New York celebrated their twin victories in May 1847. Among fireworks and illuminations, they had a “grand procession” of about 400,000 people. Generals Taylor and Scott became heroes for their people and later became presidential candidates.

Desertion

Scott's Mexico City campaign

Landings and Siege of Vera Cruz

Rather than reinforce Taylor's army for a continued advance, President Polk sent a second army under General Winfield Scott, which was transported to the port of Veracruz by sea, to begin an invasion of the Mexican heartland. On March 9, 1847, Scott performed the first major amphibious landing in U.S. history in preparation for the Siege of Veracruz. A group of 12,000 volunteer and regular soldiers successfully offloaded supplies, weapons, and horses near the walled city using specially designed landing craft. Included in the invading force were Robert E. Lee, George Meade, Ulysses S. Grant, James Longstreet, and Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson. The city was defended by Mexican General Juan Morales with 3,400 men. Mortars and naval guns under Commodore Matthew C. Perry were used to reduce the city walls and harass defenders. The city replied the best it could with its own artillery. The effect of the extended barrage destroyed the will of the Mexican side to fight against a numerically superior force, and they surrendered the city after 12 days under siege. U.S. troops suffered 80 casualties, while the Mexican side had around 180 killed and wounded, about half of whom were civilian. During the siege, the U.S. side began to fall victim to yellow fever.

Advance on Puebla

Scott then marched westward toward Mexico City with 8,500 healthy troops, while Santa Anna set up a defensive position in a canyon around the main road at the halfway mark to Mexico City, near the hamlet of Cerro Gordo. Santa Anna had entrenched with 12,000 troops and artillery that were trained on the road, along which he expected Scott to appear. However, Scott had sent 2,600 mounted dragoons ahead, and the Mexican artillery prematurely fired on them and revealed their positions. Instead of taking the main road, Scott's troops trekked through the rough terrain to the north, setting up his artillery on the high ground and quietly flanking the Mexicans. Although by then aware of the positions of U.S. troops, Santa Anna and his troops were unprepared for the onslaught that followed. The Mexican army was routed. The U.S. Army suffered 400 casualties, while the Mexicans suffered over 1,000 casualties and 3,000 were taken prisoner. In August 1847, Captain Kirby Smith, of Scott's 3rd Infantry, reflected on the resistance of the Mexican army:

Pause at Puebla

In May, Scott pushed on to Puebla, the second largest city in Mexico. Because of the citizens' hostility to Santa Anna, the city capitulated without resistance on May 1. During the following months Scott gathered supplies and reinforcements at Puebla and sent back units whose enlistments had expired. Scott also made strong efforts to keep his troops disciplined and treat the Mexican people under occupation justly, so as to prevent a popular rising against his army.

Advance on Mexico City and its capture

With guerrillas harassing his line of communications back to Vera Cruz, Scott decided not to weaken his army to defend it but, leaving only a garrison at Puebla to protect the sick and injured recovering there, advanced on Mexico City on August 7, with his remaining force. The capital was laid open in a series of battles around the right flank of the city defenses, culminating in the Battle of Chapultepec. With the subsequent storming of the city gates, the capital was occupied. Winfield Scott became an American national hero after his victories in this campaign of the Mexican–American War, and later became military governor of occupied Mexico City.

Santa Anna's last campaign

In late September 1847, Santa Anna made one last attempt to defeat the Americans, by cutting them off from the coast. General Joaquín Rea began the Siege of Puebla, soon joined by Santa Anna, but they failed to take it before the approach of a relief column from Vera Cruz under Brig. Gen. Joseph Lane prompted Santa Anna to stop him. Puebla was relieved by Gen. Lane October 12, 1847, following his defeat of Santa Anna at the Battle of Huamantla October 9, 1847. The battle was Santa Anna's last. Following the defeat, the new Mexican government led by Manuel de la Peña y Peña asked Santa Anna to turn over command of the army to General José Joaquín de Herrera.

Anti guerrilla campaign

Following his capture and securing of the capital, General Scott sent about a quarter of his strength to secure his line of communications to Vera Cruz from the and other Mexican guerilla forces that had been harassing it since May. He strengthened the garrison of Puebla, and by November established 750 man posts at Perote, Puente Nacional, , and San Juan along the National Road and detailed an antiguerrilla brigade under Brig. Gen. Joseph Lane to carry the war to the Light Corps and other guerillas. He also ordered that convoys would travel with at least 1,300-man escorts. Despite some victories over General Joaquín Rea at Atlixco (18 October 1847) and Izucar de Matamoros (in November) by General Lane, guerrilla raids on the supply route continued into 1848 until the end of the war.

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Results

Grant's views on the war

President Ulysses S. Grant, who as a young army lieutenant had served in Mexico under General Taylor, recalled in his Memoirs, published in 1885, that:

Combatants

On the American side, the war was fought by regiments of regulars and various regiments, battalions, and companies of volunteers from the different states of the union and the Americans and some of the Mexicans in the territory of California and New Mexico. On the West Coast, the U.S. Navy fielded a battalion in an attempt to recapture Los Angeles.

United States

Mexico

At the beginning of the war, Mexican forces were divided between the permanent forces (permanentes) and the active militiamen (activos). The permanent forces consisted of 12 regiments of infantry (of two battalions each), three brigades of artillery, eight regiments of cavalry, one separate squadron and a brigade of dragoons. The militia amounted to nine infantry and six cavalry regiments. In the northern territories of Mexico, presidial companies (presidiales) protected the scattered settlements there.

One of the contributing factors to loss of the war by Mexico was the inferiority of their weapons. The Mexican army was using British muskets (e.g. Brown Bess) from the Napoleonic Wars. In contrast to the aging Mexican standard-issue infantry weapon, some U.S. troops had the latest U.S.-manufactured breech-loading Hall rifles and Model 1841 percussion rifles. In the later stages of the war, U.S. cavalry and officers were issued Colt Walker revolvers, of which the U.S. Army had ordered 1,000 in 1846. Throughout the war, the superiority of the U.S. artillery often carried the day.

Political divisions inside Mexico were another factor in the U.S. victory. Inside Mexico, the centralistas and republicans vied for power, and at times these two factions inside Mexico's military fought each other rather than the invading American army. Another faction called the monarchists, whose members wanted to install a monarch (some even advocated rejoining Spain), further complicated matters. This third faction would rise to predominance in the period of the French intervention in Mexico.

Saint Patrick's Battalion (San Patricios) was a group of several hundred immigrant soldiers, the majority Irish, who deserted the U.S. Army because of ill-treatment or sympathetic leanings to fellow Mexican Catholics. They joined the Mexican army. Most were killed in the Battle of Churubusco; about 100 were captured by the U.S. and roughly ½ were hanged as deserters.

Impact of the war in the U.S.

See also

Notes

References

Bibliography

Reference works

Surveys

Military

Political and diplomatic

Memory and historiography

Primary sources

External links

Guides, bibliographies and collections

- Library of Congress Guide to the Mexican War

- The Handbook of Texas Online: Mexican War

- Reading List compiled by the United States Army Center of Military History

- Mexican War Resources

- The Mexican–American War, Illinois Historical Digitization Projects at Northern Illinois University Libraries

Media and primary sources

- Robert E. Lee Mexican War Maps in the VMI Archives

- The Mexican War and the Media, 1845–1848

- Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and related resources at the U.S. Library of Congress

- Letters of Winfield Scott including official reports from the front sent to the Secretary of War

- Franklin Pierce's Journal on the March from Vera Cruz

- Mexican–American War Time line

- Animated History of the Mexican–American War

Other

- Battle of Monterrey Web Site – Complete Info on the battle

- Manifest Destiny and the U.S.-Mexican War: Then and Now

- The Mexican War

- PBS site of US-Mexican war program

- Smithsonian teaching aids for "Establishing Borders: The Expansion of the United States, 1846–48"

- A History by the Descendants of Mexican War Veterans

- Mexican–American War

- Revolutionary War

- Quasi-War

- First Barbary War

- War of 1812

- Second Barbary War

- First Sumatran Expedition

- Second Sumatran Expedition

- Ivory Coast Expedition

- Mexican–American War

- First Fiji Expedition

- Second Opium War

- Second Fiji Expedition

- Korean Expedition

- Spanish–American War

- Philippine–American War

- Boxer Rebellion

- Banana Wars

- Border War

- World War I

- Russian Civil War

- World War II

- Korean War

- Vietnam War

- Invasion of the Dominican Republic

- Invasion of Grenada

- Lebanese Civil War

- Invasion of Panama

- Gulf War

- Somali Civil War

- Bosnian War

- Kosovo War

- Afghanistan War

- Iraq War

- War in North-West Pakistan

- Libyan Civil War

- Lord's Resistance Army insurgency

Retrieved from : http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Mexican%E2%80%93American_War&oldid=466196142